Youth, education and lifelong learning

22nd February 2017

‘Education’ and ‘youth’

It’s impossible to think of ‘youth’ without thinking of ‘education’ because young people spend so much of their time in nurseries, schools and colleges and the education they receive there plays such a formative role in their lives. Likewise, it’s impossible to think of ‘education’ without thinking of ‘youth’ – there’s something fundamental about the learning we do when we’re young which sets us up for our lives ahead and lays the foundation for us to make fulfilling transitions into adulthood.

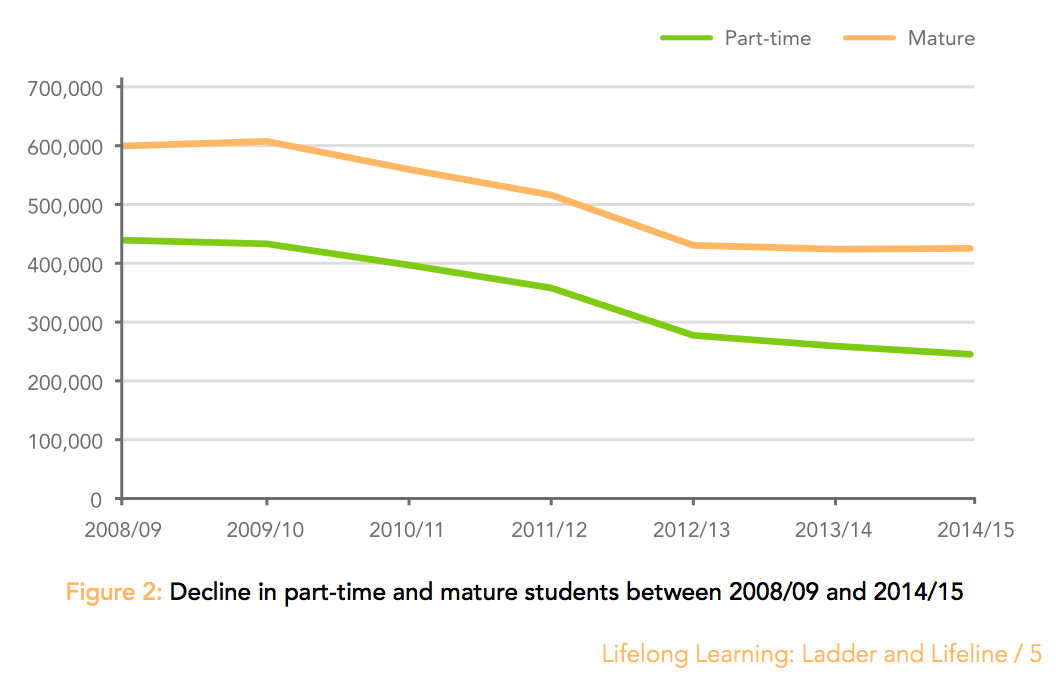

But the risk is that we overlook the importance of lifelong learning. Adult skills budgets are facing drastic cuts and rates of part-time and mature study at university are flagging. This is despite increasing need for opportunities for lifelong learning in order to react to a range of social changes, from an increasingly precarious labour market to an ageing population. Today’s report from University Alliance, Lifelong Learning: Ladder and Lifeline, is a timely reminder of the case for lifelong learning, and of the need for schools to prepare young people to continue learning well after they finish compulsory education.

Why does lifelong learning matter?

Education is inherently valuable – that’s why we have compulsory schooling, and we should apply the same sentiment to adult education. As I’ve evidenced in research for the Local Government Association, investment in adult skills is vital for supporting local economies, and should be held on a par with compulsory education. However, a perfect storm of social, economic and demographic shifts mean that formal opportunities for continuing education will be particularly crucial in the century ahead:

- At least twenty years of research have identified the gradual ‘extension’ of young people’s transitions from youth to adulthood, with young people taking longer than in the past to secure stable employment, buy a house and clear their debts. Ideas of ‘finishing education’ and ‘beginning adult life’ have eroded.

- We live amidst a more precarious labour market, with fewer ‘jobs for life’, fewer salaried jobs with stable hours, the encroaching role of automation and ever-increasing demand for retraining. Young people’s only hope of navigating this instability is to have opportunities to continuously supplement their knowledge and skills throughout life. Without these opportunities for continuing education, they will fall through the net.

- Our population profile is ageing, we’re living longer and, going by recent adjustments to the state pension age, we will also be expected to work for longer. Not only do today’s young people face greater instability in the labour market; they must also have the skills to adapt to this instability for 60 years or longer.

As well as addressing the challenges of social change, lifelong learning could also play a much more instrumental role as a lever of social mobility. Speaking at the launch of RECLAIM’s Educating All report on working class students’ experiences of higher education last week, I heard compelling arguments that students from poorer backgrounds, who tend to see HE as a higher-risk decision, would be more likely to take up opportunities to go to university if it was held up as a genuinely life-long opportunity rather than a time-limited chance.

‘Lifelong learning’ in disarray

Despite its crucial importance, the current picture of continuing education in the UK is a rocky one. Spending on core adults skills fell by 41% in real terms between 2009 and 2016, and the most recent HESA data reveal a continuing decline in part-time and mature HE study, as highlighted in today’s University Alliance report:

What can the youth sector do?

The way we educate young people could contribute to their success as adult learners later in life in at least two ways:

- Firstly, careers advice needs to move away from a simple ‘aspirations raising’ mantra, which focuses on moving young people bluntly towards specific ‘high status’ educational and career paths, and instead embrace the notion of ‘planned happenstance’. This approach encourages young people to have a range of aspirations, to work as hard as they can to achieve them and, as a result, be ready and resilient for change if ‘plan A’ doesn’t come to fruition.

- Schools are the crucible in which people’s lifelong attitudes to learning are forged, as any parent who shudders at the sight of the school gates or the thought of a classroom will testify. Undue focus on high-stakes testing and a narrowing of the school curriculum risk an ‘across the line!’ attitude to learning, rather than imbuing young people with a love of learning and a confidence for independent inquiry – skills that are crucial in the modern economy.

As a society, we tend to see ‘learning’ as something that takes place when we’re young. Besides, compulsory education ends when we finish our teenage years. Nothing symbolises this more than current debates around education spending, which have focused almost exclusively on school budgets and largely glossed over the far-larger cuts to adult skills spending. Social change demands that we shift this perspective and embrace compulsory education as an opportunity to prepare young people for a lifetime of learning, rather than a period of training which ends abruptly at 18.

Comments