How will the government respond to our assessment recommendations from #TestingTheWater?

30th November 2017

The government has today responded to the Education Select Committee’s report on primary assessment and in doing so, picked up on numerous themes from our new report, #TestingTheWater.

1. Testing the Water calls for headline league tables to shift to three year averages.

Doing so would reduce the impact of year on year volatility (based on the school’s cohort of pupils or other variation), and reduce the chances of schools chasing short term gains. The Education Select Committee has made a similar call.

The government has highlighted the fact that it has published three-year averages “as additional measures” but I just don’t think this is enough.

They are right that publishing three year averages right now is impractical (and largely impossible) due to recent changes to the measures. So I’m pleased that they say “our intention is to return to publishing three-year rolling averages” however it is crucial that once published, these become the headline measures.

2. Testing the Water calls for the establishment of a National Assessment Bank

An assessment bank would provide high quality formative and summative assessment materials, saving teachers time and ensuring the right tools were used for the right purposes. It would also ensure high stakes exam materials like past test papers became less dominant.

We are therefore encouraged to hear that the government will “consider the case for the creation of a national assessment bank”

3. Testing the Water calls for any assessment and accountability reforms to be introduced over an extended, planned period of time.

In some other countries, reforms are introduced over 5 year periods yet in England, teachers are constantly playing catch up. This creates workload, stress and poor implementation.

The government today admits its approach “has been stretching for schools, teachers and pupils.”

Whilst this is putting it mildly to say the least, I’m glad they say they “accept that the changes were not always communicated as well or as quickly as they could have been”. It’s therefore encouraging that “there will be no new national tests or assessments introduced before the 2018 to 2019 academic year”.

On the other hand, they also say:

“The Department’s Protocol for changes to accountability, curriculum and qualifications sets out that there should be a lead-in time of at least a year for any accountability, curriculum or qualification initiative that requires schools to make significant changes”

This fails to recognise that a year is very little – particularly when teachers are having to re-plan swathes of the curriculum, time and again!

4. In Testing The Water we highlight the fact that using summative assessment formatively and vice-versa is distorting and unhelpful.

Using tracking data to generate summative gradings is inappropriate and inaccurate. It also leads to an obsession with grade boundaries.

The government’s statement admits that:

“Levels came to dominate all assessment and teaching practice. This had a damaging impact on teaching and failed to give parents an accurate understanding of how their children achieved in school”.

It therefore argues it has had to avoid “inadvertently imposing a new national system of formative assessment on schools, to allow schools to design assessment systems that work for their pupils and curricula,” but that it has given guidance through its Commission on Assessment Without Levels.

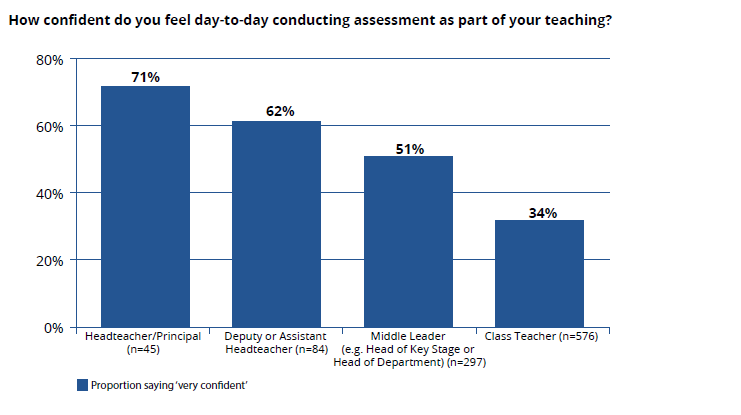

However, Testing The Water uncovered low levels of confidence and knowledge when it came to assessment and widespread poor practice. It is therefore far from clear that schools and teachers have developed the expertise needed to invent and implement effective new systems.

Hopefully the government’s commitment to “supporting the school system to make the transition from levels” means it will back our calls for schools and teachers to receive the resources and training they need in order to do this. A mention of “an online training module on in-school assessment… aimed at classroom teachers, school leaders, governing bodies and teaching schools” could also help.

Hopefully the government’s commitment to “supporting the school system to make the transition from levels” means it will back our calls for schools and teachers to receive the resources and training they need in order to do this. A mention of “an online training module on in-school assessment… aimed at classroom teachers, school leaders, governing bodies and teaching schools” could also help.

5. In Testing the Water we ask “how can unnecessary stress about assessment be reduced for young people and their teachers?”

We call for schools to:

- use more low stakes assessments.

- decouple pupils’ test results from teachers’ performance evaluations.

The government’s statement says:

“we do not recommend that (schools) devote excessive preparation time to assessment”

Clearly I agree with this sentiment but it is hardly surprising that they do, given the context they work in.

One thing that is hugely important is not tying teachers’ pay to pupils’ test marks and it is good to see that the government is reiterating that this is not the expectation. It explains that factors to take into account could include:

”a range of factors beyond key stage 2 results alone, including wider outcomes for pupils, improvements in specific elements of practice (such as behaviour management or lesson planning), impact on effectiveness of other staff, and a wider contribution to the work of the school.”

All things considered, it seems things are moving in the right direction and the government seems to be somewhat open to our calls. Hopefully it will now consider each of our recommendations in turn and take action wherever possible.

Please take a look at our full report and let us know what you think, using ‘#TestingTheWater’.