Teachers and professional development: Where’s the appetite for CPD?

29th June 2017

On a panel for the Education Policy Institute at last week’s Festival of Education I spoke about teacher professional development. I highlighted a key conundrum that must be solved if we are to raise the bar, both in terms of teachers’ access to development opportunities, and the quality of these opportunities.

I call this conundrum the ‘appetite problem’ and it arises because teachers just don’t seem to care about CPD as much as one might expect.

The conundrum

In our Oceanova report, “The Talent Challenge”, we argued that a silver lining to the current teacher recruitment crisis could be schools prioritising attracting and retaining teacher. Thus, rather than improvements in professional development having to be driven by yet more regulation and government edict, change might come from within the system. This could help avoid more box-ticking and disruption whilst prompting a change of gear when it comes to CPD.

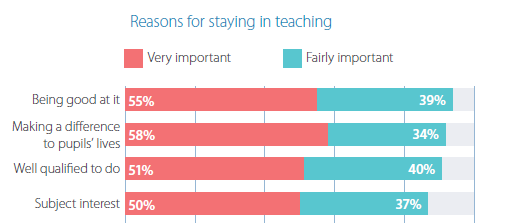

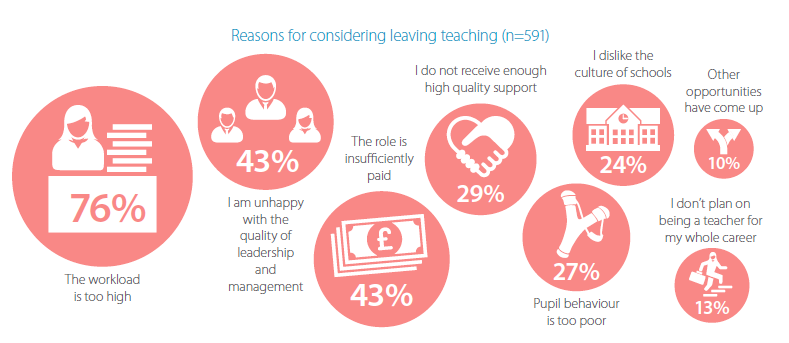

On one hand, evidence suggests that teachers ‘should’ care about CPD since they are passionate about doing their job well. Our “Why Teach?” report showed that the top three reasons why teachers stay in teaching are “Being good at it”, “Making a difference to pupils’ lives” and “Being well qualified to do it”. Each of these was cited by over 90% of respondents. Over half said these three factors were ‘very important’. Surely CPD is fundamental to each of these? Furthermore, when we asked people why they had considered leaving the profession, almost a third said that a lack of high quality support played a role.

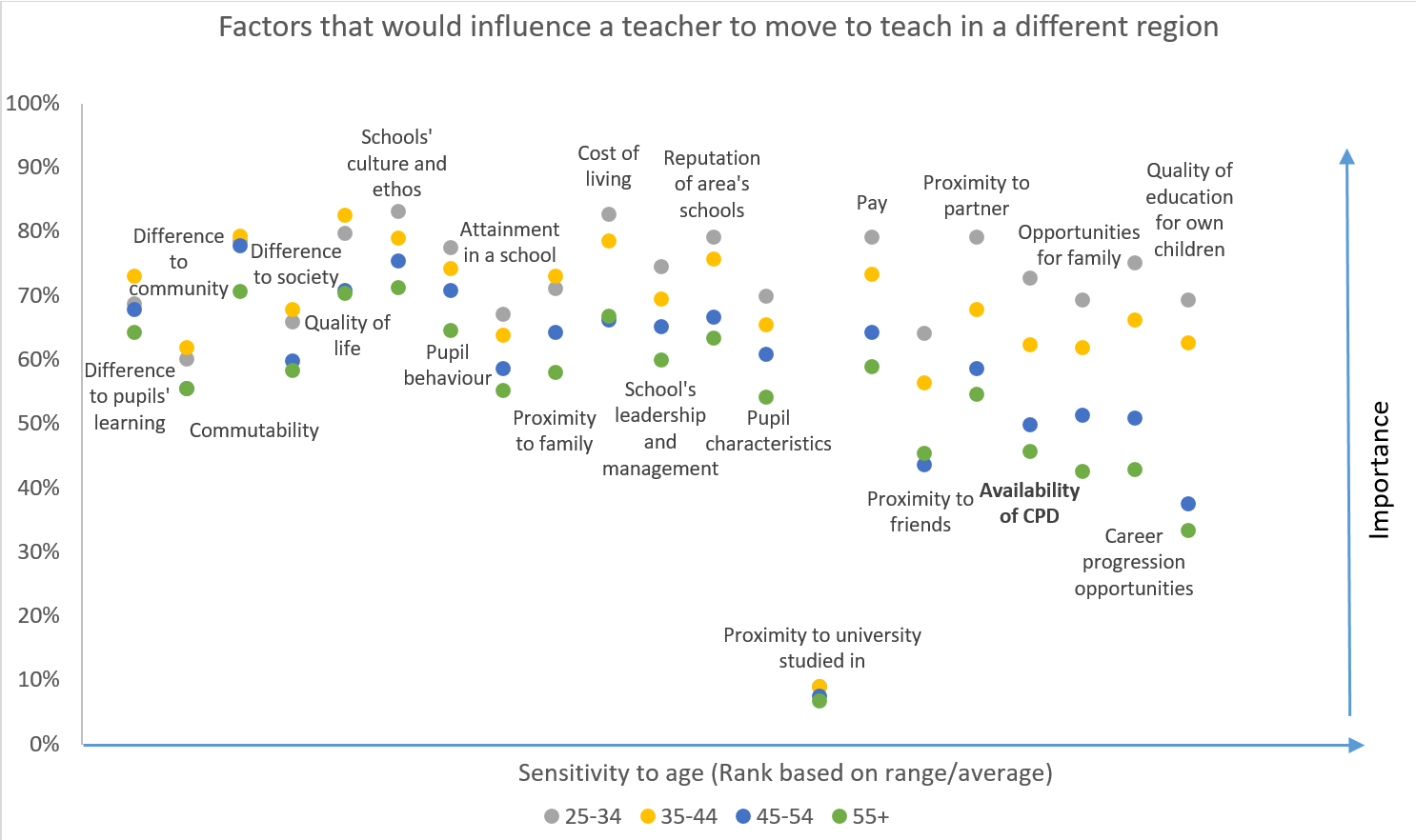

Given this, one might expect every teacher to be clamouring for more CPD. Surely they should be knocking down the doors to work in schools offering good opportunities. Yet this is not the case. When we asked teachers what had influenced their decision to teach in their particular town or area, CPD came 15th out of 21 factors. When we asked them what would influence them to move to teach in a different area, it came 17th out of 21.

It could be argued this is because professional development is a school-based factor rather than an area-based one. Perhaps it is only the latter that matter when picking where to live and work. However, other school-based factors, like the quality of leadership and management, pupil behaviour, and the schools’ culture and ethos came well ahead of CPD in our survey responses. So the conundrum is that teachers’ desire to be great at their jobs is not translating into a desire to work in schools offering the CPD that should help them excel.

Age sensitivity

In order to understand this better, as is so often the case, we need to dig below the averages by looking at how appetite for CPD is distributed. One way of doing this is to see how interest in different factors varies by age.

Doing so, reveals that appetite for CPD is one of the four most age sensitive factors: whilst availability of CPD would influence three-quarters of 25-34 year-old teachers’ decisions about where to work, this was the case for less than half of 55+ year-old teachers. Whilst it is hardly surprising that younger teachers are more willing to move, what is striking is that the age-effect is stronger for CPD than it is for many other factors. Furthermore, two of the other highly age-sensitive factors were clearly linked to family life and children, whereas this is less obviously the case for CPD.

So why is appetite for CPD so age sensitive? I think there are two reasons. Firstly, once bitten twice shy. We know from CUREE’s work, the Teacher Development Trust and mountains of anecdotes, that a lot of CPD is awful. Given how many dreadful sessions veteran teachers will have sat through, it is hardly surprising that they lose faith in the possibility of finding decent professional development. Secondly, could teachers’ ambition taper off as they get older? The diagram above shows that sensitivity to ‘opportunities for career progression’ is also very age sensitive factor, which might lend weight to this interpretation.

Implications

Appetite is key, and if improvements in CPD are to be driven by the profession rather than by government. The findings above therefore point us towards two conclusions:

- Teachers need to get a taste of the promise: they need to believe that CPD can be good. This will only happen if they experience good provision. Schools therefore need information on what CPD might be good. Whilst the government shouldn’t mandate for CPD, it should help build the infrastructure that provides the necessary information. This is where the Chartered College of Teaching could play a role.

- CPD needs to be sensitive to teachers’ professional life-cycles: whilst newer teachers may have an appetite for CPD based on their desire to progress through the profession, not all older teachers share this desire. They may therefore be more motivated by the opportunity to develop mastery of the craft of teaching, or by their desire to support pupils better (something teachers at every stage of their career are passionate about). A persisting interest in a subject could also act as a motivator for older secondary school teachers. This would be another reason to welcome calls from commentators like Stuart Lock for more subject-specific CPD.

Ultimately teacher appetite should be the driving force behind improved CPD. The professions’ underlying motivations suggests this appetite could be lurking just under the surface, and perhaps growing interest in Teach Meets and #UKEdChat is a sign that such interest is starting to be awakened.

Comments