School Residentials: enrichment and inequality

by Loic Menzies

29th September 2017

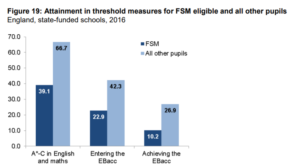

We all know that education in England is riddled with inequality. The statistics are out there, painted in stark figures and depressing graphs. But can educational inequality really be reduced to 27.6 percentage point gap in A*-C in English and Maths?

We all know that education in England is riddled with inequality. The statistics are out there, painted in stark figures and depressing graphs. But can educational inequality really be reduced to 27.6 percentage point gap in A*-C in English and Maths?

Unfortunately, it often has to be, because measuring and comparing anything broader in concrete, objective terms is nigh on impossible.

However our new report, published today finally provides figures from tens of thousands of schools and reveals a rather different sort of gap.

Using data from the Evolve system (used by tens of thousands of schools and other youth organisations) as part of our work for Learning Away’s Brilliant Residentials campaign, we show that poverty skews and considerably limits pupils’ opportunities in school.

The leveller

Education should be a great leveller. Schools should enable disadvantaged pupils to access opportunities that they might never experience otherwise – and of course most do. However, our analysis shows that schools serving disadvantaged communities run far fewer residential trips for their pupils and that even when they do, only a third of teachers are confident that their pupils could all afford to participate. We also found that schools organise slightly different residentials depending on the deprivation of the communities they serve.

Residentials and deprivation (n=9,975)

Affordability of residentials (n=610)

Access to residentials is just one example of an enriching experience that we might want pupils to access. However, it is invaluable to finally have concrete, large-scale data on something that might otherwise be treated as an ‘intangible’ that cannot be measured or compared.

It is just one way of demonstrating that educational inequality goes beyond attainment.

I was lucky enough to teach in a highly disadvantaged school that received generous corporate sponsorship for residential trips. I also somehow became known as one of the teachers who was up for running these trips. I therefore experienced first-hand just how eye-opening these trips can be for pupils, how they change a group dynamic and give young people a whole new perspective on life.

To think that the pupils who might most benefit from these experiences are those who are most likely to miss out is deeply unjust.

Our report therefore concludes with the following recommendations:

- Schools should be encouraged to use pupil premium funds to provide equality of opportunity, not just to close the attainment gap.

- Funds should be made available to schools to ensure there is fair access to residentials for all pupils.

- Schools should carefully put together a range of strategies to ensure fair access including:

- Cost reduction and use of lower cost options (e.g. in Autumn and winter, or nearer to home/on school grounds);

- Communication with parents to identify and plan for any financial need;

- Targeted and universal subsidies;

- Flexible payments to ensure all residentials.

- Schools should pay particular attention to ensuring that ambitious foreign trips are equally accessible to all pupils.

- Schools should be careful of equating the national curriculum with the school curriculum. By including residentials as part of the latter they could ensure access is equitable and that pupils’ skills progress.

You can download the full report here , the press release here or read the executive summary below.

Executive Summary

1. The availability of residentials

1. The availability of residentials

Each year, only a small minority of school pupils experience a residential trip and pupils in the most disadvantaged areas are the most likely to miss out.

On average, educational establishments organise 2.5 residentials per year. We therefore estimate that approximately 1.8 million children and young people are involved in residentials each year. This is equivalent to 21% of the school pupil population. Whilst this probably means that in most schools, at least some pupils are involved in a residential each year, it also means that every year, a large number of pupils do not experience a residential. Unfortunately, we find that it is pupils in disadvantaged areas who have fewest opportunities to participate.

2. The purpose of residentials

Residentials are frequently focused on personal development, and less so on curriculum subjects. Pupils access different types of residentials depending on their area’s socio-economic characteristics.

Nationally, the most common purposes for residentials are to impact on personal development or to deliver the Duke of Edinburgh award. In 2016, these two categories combined to account for a third of residentials. Subject focused residentials are less common, but amongst these, Humanities subjects tend to dominate. In the most deprived areas, pupils are more likely to participate in “Personal Development” and PSHE focused residentials and less so the Duke of Edinburgh award.

3. The quality of residentials

Residentials are generally of high quality but cost is stopping many poorer pupils from participating, leaving them doubly disadvantaged in terms of their participation.

In this report, Learning Away’s agreed characteristics for a “Brilliant Residential” serve as a benchmark for quality. We find that design and planning of residentials is an area of strength although pupils’ involvement in planning is very much limited. There are however serious concerns in relation to affordability and this problem requires urgent action, particularly given that there is considerably guidance available on providing low cost, high quality residentials.

We find that pupils from poorer families are doubly disadvantaged when it comes to residential provision: they are more likely to live in areas where fewer residentials are available and costs mean they are less likely to be able to participate where they are. Schools are attempting to address this problem, (often by using the pupil premium). However even where teachers try to make residentials affordable, they still consider cost to be a barrier to participation. As funding is squeezed, this will become an increasing problem.

Not all teachers want to use structured approaches to evaluation, however some who wish to do so are not sure how to go about doing so. It can be particularly tricky to reflect and evaluate thoroughly when residentials take place at the end of a summer term – which many do.

Almost half of residentials are mainly led and delivered by external staff. Teachers frequently noted that their involvement in planning was limited by the fact that they were using an ‘off the shelf’ activity.

Teachers do not necessarily see co-planning with pupils as desirable, furthermore, even where they want to involve pupils, they face practical barriers. In many cases they seek to overcome these by drawing on pupil feedback from previous years.

For many teachers, residentials occupy a position that is distinct from the standard curriculum. This sometimes limits teachers’ willingness to link residentials to the curriculum or plan for progression.

Comments