Question #6 – What rule best predicts teacher ‘behaviour’ ratings of pupils?

23rd January 2014

In all my time as a teacher, what was the topic that received the most staffroom discussion? Pupil behaviour. And Saturday’s Touchpaper Party was no exception. The difference at the weekend was that my group (Loic Menzies, David Weston and myself) were trying to answer the question above. We drafted a model and formula (explanations to follow!) although I think it’s fair to say that we ended up asking more questions than we managed to answer. If anyone’s looking for a PhD topic, look no further!

Here’s the beginning of our thought process:

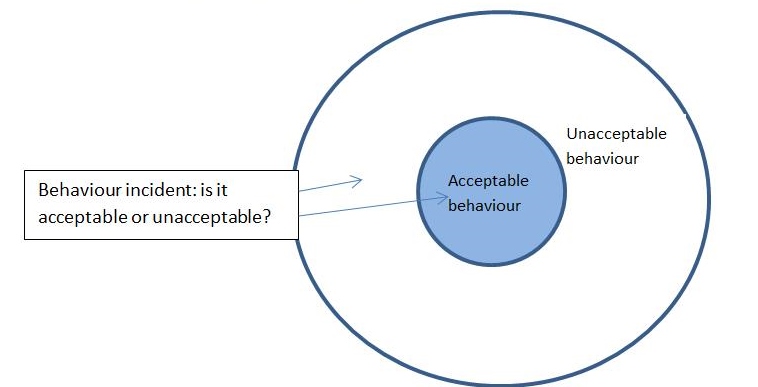

How do teachers categorise behaviour incidents?

Whenever a teacher is presented with a behaviour incident, they will categorise it as either acceptable or unacceptable, placing it in the inner or outer circle of this model.

Over time, the teacher will come to a decision about the overall behaviour rating they would give a student based on these incidents, although as I explain later, there are other factors that contribute to this rating too.

The boundary on this model will obviously change from teacher to teacher but even once set, it is unlikely to be applied with clinical objectivity. For example, one teacher may generally consider shouting out acceptable, another not, yet there will also be cases where a normally tolerant teacher may find an incident of shouting out unacceptable based on the kind of day they’ve had, their relationship with the student or even whether SLT are on a ‘learning walk’. Recognising the distinction between setting the boundary and interpreting the incident has important implications for ‘being consistent’. Pupils forever stress the importance of teachers being fair and we know that being consistent is key to promoting good behaviour. As a result, many teachers put great emphasis on setting clear rules (establishing the boundary of acceptable behaviour). However, our two part model suggests it is equally important to interpret incidents consistently and draws teachers’ attention to the changing internal and external factors that can influence that interpretation.

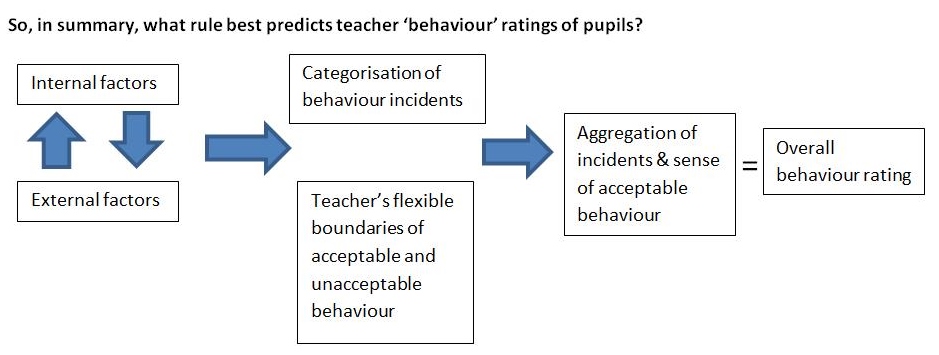

So what are the factors that influence how we categorise incidents and rate behaviour overall?

To break down how teachers categorise and rate behaviour, we came up with a list of internal and external factors. We considered the internal factors to be things such as: educational background of teacher; ability to build rapport; race, gender, class of teacher or teacher’s belief in self efficacy. Some of the external factors include : the school behaviour policy; the time of day; the pupil’s race, gender and class or the family history of the pupil.

The dynamic between the internal and external factors can be interrelated. For example, a pupil’s race is an external factor, but how the teacher responds to that will depend on their values and upbringing, so it is therefore internal too. David Gillbourn has done some fascinating and controversial work in this area, considering how our perceptions of race influence how we react to pupils. Another example could be if a school has explicitly defined what constitutes unacceptable behaviour (external factor), it may be that the teachers are more united in how they categorise incidents, despite their own internal definitions.

A case in point is the school I trained at: when teachers were rating behaviour there was a strong emphasis on internal, subjective factors as the behaviour policy wasn’t clearly defined. For me, a clear example of unacceptable behaviour was fighting. However, for teachers who had been exposed regularly to such behaviour, they had different levels of what was ‘acceptable’ depending on their relationship with the students, the severity of the fight and where it had taken place.

By the end of the year, a strict behaviour policy had been put into place: non-school uniform was taken seriously, as was mobile phone use. Even if teachers internally felt that this behaviour was acceptable, they had to enforce the school’s policy and sanction the behaviour, contributing to their overall ratings of pupils. Discussions around behaviour ratings became a lot more explicit and consistent as there was a clear external policy in place, even if some of the staff’s internal consideration of behaviour differed. This, in turn, affected how the pupils behaved, changing the dynamic and relationships between staff and pupils for the better.

What else affects how a teacher aggregates behaviour incidents into an overall rating?

There are a number of factors that contribute to the teacher’s overall rating. For example, a teacher that keeps meticulous records may realise a pupil has improved over time, instead of just remembering the last incident. Furthermore, if there was an incident that a teacher had a strong emotional reaction to, it may well be that this clouds their judgement for better or worse. There could also be the effect of peer influence. A teacher that hears, “Oh, she’s never like that for me,” from a colleague may modify their behaviour rating accordingly.

Is there any research on this?

An initial hunt on Saturday seemed to indicate that there is plenty of research on types of unacceptable behaviour but there’s not a lot on what factors influence how teachers perceive behaviour. There are some starting points here and here but if you’ve got any further suggestions, I’d be keen to hear more in the comments section below.

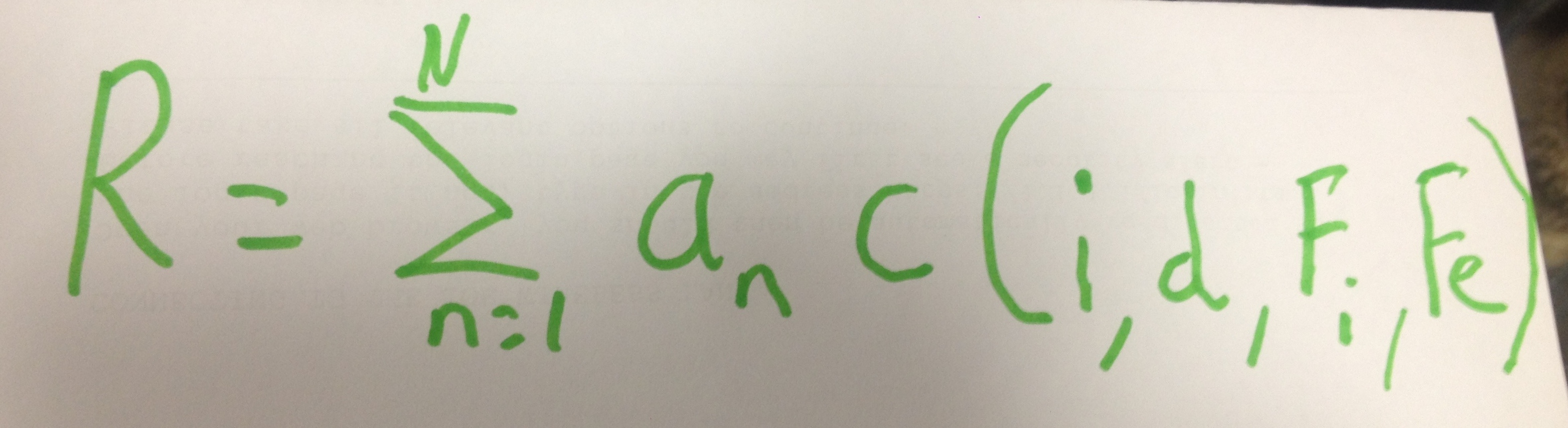

Or, of course, if you prefer the geek version, here’s Loic’s crazy formula. But for more on that, you’ll have to ask him directly at @lkmco!

Final conclusions:

This is just the starting point: from here the next step is to carry out research that explores the weighting of internal and external factors and the relationship between them. One of the last questions Laura asked was ‘What would it take for you spend 100 hours on your question?’ For me the biggest motivator will be discussing and reflecting on it regularly. So… leave your comments below and we can take it from there. And it’s no longer 100 hours: I’m on 92 and counting.

Comments