Grammar Schools for the Bright but Poor: Why they wouldn’t help either

12th August 2016

Would I be happy with grammar schools if they exclusively served bright-but-poor pupils? This is one of the questions I was asked following my “Uncle Steve” blog.

The answer is “no”. Whilst grammar schools’ socio-economic skew is one of their flaws, it is not the only one. We need to ask what problem grammar schools, exclusively for disadvantaged pupils would be trying to solve and how it would all work in practice.

Insufficiently high school quality overall

If the problem is that schools are generally not good enough, the solution certainly isn’t taking out a small proportion of the most motivated and able pupils. All this does is make it even harder for the vast majority of schools and pupils to succeed. The vast majority of schools that are not grammars would benefit from fewer positive peer effects and struggle even more to recruit teachers.

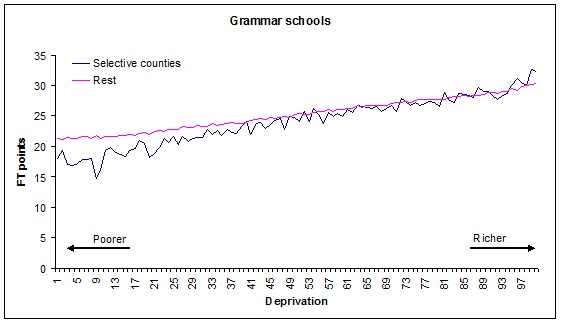

Several counties already have a selective system and as Chris Cook has shown (and FullFact recently reported), the evidence for grammar schools’ impact on overall school quality hardly looks promising.

The unmet needs of bright-but-poor pupils

It might be argued that grammar schools are needed because super-bright kids are so far from the norm that they have a particular set of needs that can’t be catered for elsewhere.

I understand that where pupils have such profound needs that they can’t be educated in mainstream schools we sometimes send them to special schools. Some might therefore say the same applies to the opposite side of the ability distribution. However it’s not true that super-bright pupils can’t succeed in mainstream schools and specially designed schools for the bright-but-poor would come at a cost. As Laura McInerney has asked, why do we think ‘bright-but-poor’ pupils are specially deserving of the huge investment needed to reshape the school system around their needs?

The most able pupils are often better placed to succeed given that they’re more likely to have parental support, more likely to have the ability to push themselves forward, read independently etc. Why would we therefore spend vast sums on creating schools specially for them, to the detriment of poor-but-average pupils? This question is particularly critical at a time of shrinking budgets and when we don’t have enough vanilla-variety schools to cater for our growing school age population. As Jonny Walker has argued our obsession with this particular small group seems to comes from a desire to maintain an illusion of meritocracy.

Instead, our priority should be to improve provision for highly able pupils across schools rather than simply removing a fraction of them. Creaming off a few would simply leave borderline peers, who may be very bright but don’t quite make it beleaguered in schools no longer expected to cater for the more able.

Aside from those issues there are also three practical questions to ask:

1. Who are we identifying as poor?

Poverty is not a binary but getting into a grammar school is. Poorer pupils perform worse at every point in the income distribution so any cut off point for eligibility for a school for the bright-but-poor would be arbitrary.

Furthermore, such a policy would cause no end of perverse incentives. How long do you have to be poor to be eligible? Might it be worth taking an income cut for a while to qualify? And what happens if you stop (or start) being poor half way through secondary school?

2. Who are we identifying as bright?

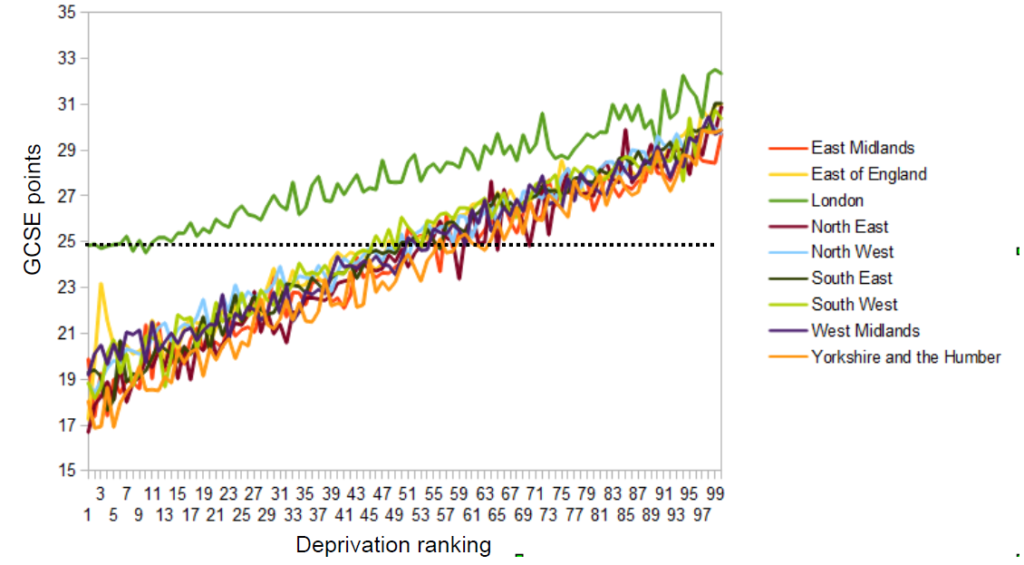

Yes genetics and innate ability play a role. However, when we test kids aged 11, their level of attainment usually tells you more about how supportive their parents are; what sort of an upbringing they’ve had; how long they’ve been in the country; what has or hasn’t gone wrong in their life; how good their primary school was; and whether their parents decided to save all the money they could to pay for tuition. Even amongst poorer pupils a selection test would largely pick out the ‘least disadvantaged’.

3. Is it in their interest anyway?

What sort of preparation for life is it to spend your school-years exclusively surrounded by other super-smart people? Wouldn’t it be better for you to develop your talents whilst also learning to interact with a range of people, developing your ability to explain ideas to others and understanding the wider society you live in?

The last thing we need right now is to further cut up the country along ‘intellectual’ divides.

Whilst elite schools for the bright-but-poor might sound tempting, the truth of the matter is that selection is neither practical nor panacea.

More from LKMco on Grammar Schools

Deputy Director Anna Trethewey on why she’s pleased her mum kept it comp

A wonderful article but facts and logic seem irrelevant to this debate.

Just to add: I got a brilliant reaction to this that I wrote on Mumsnet

It’s one of the very nasty double standards around this debate that whilst we’re supposed to pity the bright kid in a bad comp who is supposedly ruined by that experience and will spend their life scarred by the memory , the kid in the bad SM is meant to treat their failure and subsequent bad education as a valuable learning experience.

It was in response to someone saying how failing the 11+ could be good for you. The debate is too important for false modesty, so if there’s something in this phrasing that hits the spot, please use or adapt it

You state that “selection is neither practical nor panacea” yet selection for admission to some schools – as far as I am aware – according to musical, artistic or sporting ability is still practised whilst selection by academic ability it is not. Is this not inconsistent?

That’s true- though they can only select 10% by aptitude- so it’s still pretty different.