Getting research into policy: the role of think tanks

30th May 2018

Last week I joined a panel at the Kaleidoscope conference in Cambridge University’s Faculty of Education. The session, which also featured Rob Loe and Hwa Yue Yi, focused on the role of think tanks in education research and policy. The panel was asked to comment on four questions:

Potential: What do think tanks and similar organisations have to contribute to education?

Potential: What do think tanks and similar organisations have to contribute to education?- Pitfalls: What are some of the main challenges/obstacles to the work they do?

- Partnership: What is the relationship between independent research institutes and academia? How can they work together?

- Getting in there: What would you say to graduate students wanting to enter the sector?

This post summarises my comments (whilst nicking some of the other panellists’ best ideas).

Potential: what do think-tanks and similar organisations have to contribute to Education?

I began by explaining that I was in many ways a ‘think tanker by accident’. I had not particularly intended to work in this space but had gradually moved into it, partly as a result of recognising an important need.

What underpins that need is the fact that those working in education, (both at policy and practitioner level) require ideas that are based on research and a birds-eye view of what is going on in the sector. The think tank niche therefore involves shaping policy by providing timely, applicable and accessible solutions to policy challenges.

1. Timely: New questions, issues and policies come to the fore in a rapid-fire manner and it is important to offer quick, evidence-informed scrutiny. Timescales for academic research are generally measured in months or years – which is important in building up a knowledge base over time, but when Education Secretary Michael Gove was popping urgency pills and making multiple announcements every week, we at LKMco tried to respond within hours.

This meant making the most of what evidence was available and drawing together a response based on our understanding of the sector. Overall, it ensured that policy makers knew they were being watched and (hopefully) helped constrain some of the worst excesses..

2. Applicable: As I’ll explain later, I find this one of the trickiest things to negotiate. The role of think tanks is not just to describe what should happen in an ideal world, but to propose applicable steps that will move the system towards it. A think tank report on improving the special educational needs system that proposed “reframing the neo-liberal discourse underpinning the contemporary system by tripling per pupil funding and empowering pupils to pursue self-directed fulfilment” would be unlikely to make a mark, or result in change.

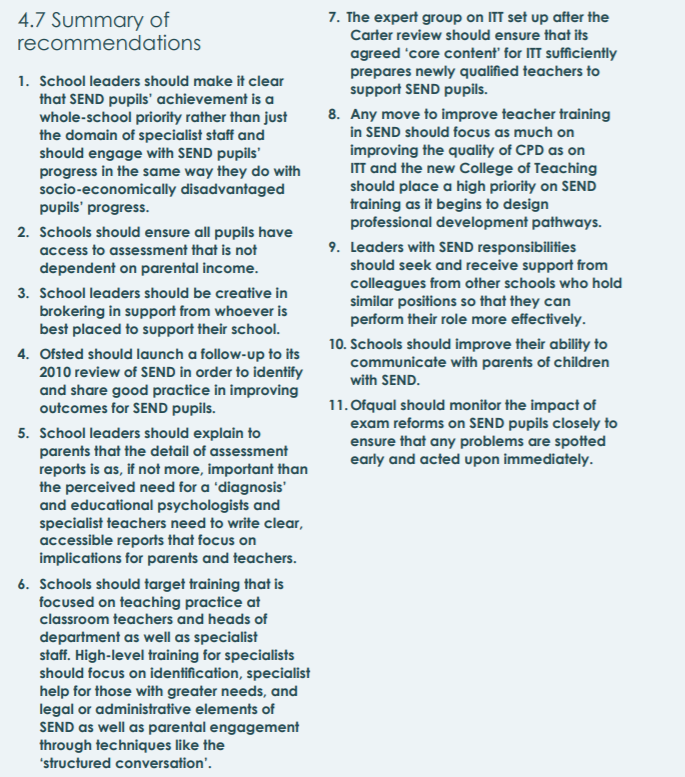

The recommendations in our 2015 SEND report “Joining the Dots” (below) were perhaps more prosaic, but they took the current state of affairs as their starting point and built on this. That’s not necessarily the right thing for everyone to do, but it’s the niche we occupy.

3. Accessible: I often ask our team to imagine their reader running through Westminster tube station reading a blog (this blog?), on their phone as they rush to a meeting. We therefore need to communicate our ideas in clear, short (much shorter than this blog) pieces.

In contrast, even the abstracts of academic articles would pose a challenge to such a reader. Think tanks therefore have to present research and thought-leadership in an accessible way, whether through high-traction press releases, blog posts, tweets or even podcasts and Instagram posts.

Pitfalls: What are some of the main challenges when doing this type of work?

As a ‘think tanker by accident’, part of the problem has been not knowing the ‘rules of the game’. Who knew, for example, that when you publish a report you should call up relevant ministers/advisors/civil servants to talk through your recommendations? Or, that you should submit responses to government consultations? Getting better at all of this is a key strand of our current three-year strategy.

Two other challenges are how our work is commissioned and balancing applicability and idealism.

- Commissioning

Unlike many traditional think tanks, our work is generally commissioned by organisations. They come to us because they think we are well placed to understand the big questions they are grappling with (and in the interest of openness we list our clients/funders each year in our social impact report).

The advantage of this is that it ensures we answer questions that matter and that are relevant to people in the sector. The downside is that where our birds-eye view tells us there is a big issue that needs addressing, we can’t do much about it until someone commissions a piece of work. This inhibits timeliness.

We try to work around this in a number of ways. For example, we self-funded and self-published a report on schools and social cohesion in the wake of Brexit; a booklet on Free Schools when this policy was all the rage; and now, we are working on a Mental Health report. This is part and parcel of being a registered Community Interest Company that reinvests its income in social impact.

Another approach was to secure rapid support from Pearson for ‘Why Teach?’ when the recruitment and retention crisis first reared its head. These are limited solutions though and we are now looking to establish an independent research fund to help us do more of this type of work (please contact us if you’re interested!)

Another potential downside of commissioning is the risk that it compromises independence. However, we have generally been lucky in terms of clients’ commitment to research integrity and we also insert some nifty clauses into our contracts to guard against potential problems.

- Idealism versus applicability

This is the biggy for me, and, to explain it, I shared two examples with delegates. Hopefully these help demonstrate the ‘realpolitik’ of policy-making.

The grid

First was ‘the grid’ and it turned out that very few attendees had heard of this. It is essentially a table in Number 10, setting out every day, which department will make what announcements when. This is a key mechanism by which government controls the news cycle and plays a role in the proliferation of random pots of money that are allocated to specific projects in order to provide government-friendly headlines. Thus, traditional think tanks (who often measure their influence in terms of how many of their recommendations are translated into announcements), often look for technical (and sometimes gimmicky) suggestions that are well suited to the grid, whether or not these are really the best way of improving the system.

Austerity

Secondly, I shared an anecdote from back in 2011 when a think-tanker told me that, given the climate of austerity, they were banned from making any proposals or recommendations that required extra funding. This was a common approach at the time and is an extreme reading of the ‘applicability’ point made earlier. Fortunately though, what counts as an applicable step changes with the political climate.

As an idealist rather than a technocrat, my response to this challenge is to pursue ‘idealism by stealth’. Firstly, as a ‘think and action-tank’ we believe that there is more than just the policy lever out there; our reports therefore set out steps that practitioners (such as schools and social services) can take to move things along, regardless of how palatable our ideas are at a policy level.

I also believe that a system can be nudged along by being media-savvy and relentlessly raising issues to get them into the headlines. It is no accident that politicians are finally starting to talk about exclusion and special educational needs; parents, SEND organisations, thought leaders and think tanks like us have been banging this drum for years. Our research shows that this has gradually helped ‘shift the zeitgeist’. Think tanks can therefore re-frame conversations and expand the range of possible – and necessary – options.

Another approach involves what I would describe as ‘co-opting the agenda’. Understanding policy makers’ agendas, means think tanks can pursue their idealist visions by pegging them to politicians’ priorities.

For example, we know that arguments framed in terms of ‘what parents want’; ‘productivity and the economy’; and, ‘value for money’ tick important boxes for policy makers. An issue like reducing school exclusion can therefore be set out in relation to these themes in order to maximise traction. This is a distant cry from most academics’ remit.

Stealthy idealism and co-opting the political agenda: research, think tanks and education policy Click To TweetPartnership: What is the relationship between independent research institutes and academia and how can they work together?

The first thing to note is how limited I think the interaction is. The two inhabit different worlds, speaking different languages, attending different events, and, unfortunately, not always treating each other with respect. However, there are three important ways they can and should work together.

- Most of our projects begin with some sort of literature review. These involve ploughing through vast tracts of academic research. Academia therefore feeds into our work in an important way at this point. Academics should therefore see think tanks as a important allies in translating research into policy and follow the advice set out in this post.

- I think academics should pursue a second approach more than they do at present: by scanning which think tanks, thought leaders and policy makers are working on fields related to their own, academics can identify potential audiences for their work. Carefully monitoring education news through trade-press (such as the TES and Schools Week) and social media would help them spot when an issue they are working on is in the news. This is the time to proactively contact the individuals involved in order to flag relevant research.

- The third approach is one that we have explored recently at LKMco. Because our work has to be timely we rarely exhaust the possibilities of the large quantity of data that we gather. We are therefore keen to share and re-use this data (in GDPR compliant ways), partly by working on follow up articles and academic publications with academics. For example, following the publication of ‘Why Teach?’ we returned to our data with Charleen Chiong (a PhD candidate at Cambridge’s Faculty of Education) and published an article in the British Educational Research Journal, on long-serving teachers. We would love to do more of this and currently have a couple of articles in the pipeline.

Getting in there: what would you say to those looking to enter the sector?

- Follow the policy world: read the trade press, follow key people on twitter (See this list from Sam Freedman / or this list from Ross McGill ).

- Make your own work accessible: Whilst conducting research on young people’s aspirations I stumbled across this blog by a young PhD researcher named Sam Baars, I was impressed by the clear communication, solid research and beautiful presentation. A few years on, Dr Sam Baars is now our Director of Research.

- Those who ask, get: Every week I receive emails from people interested in working with us. I tend to ask them to send over a CV and some thoughts on why they’re interested. I then keep their CV so that next time we have enough funding to employ someone new, I can get in touch. The people who get in touch have already demonstrated their initiative and those who particularly stand out are:

- Those who have clearly followed steps 1 and 2 above.

- Those who send something tailored to us rather than generic, i.e. which explicitly linking the work we do to their interests and expertise.

- Those who have a good mix of skills and expertise e.g. working with young people (we mainly employ ex-teachers and youth workers), producing research, using quant and qual methods.

- Those who communicate like friendly humans.

All in all, it’s increasingly clear to me what an important role think tanks and similar organisations play in the world of education policy. I was recently at an international conference of people working in education policy run by Teach for All. I was struck by how many people from other countries bemoaned the lack of organisations like LKMco in their context, so long may it continue!

Comments