When and how do children learn prejudice?

12th December 2017

I was shocked by the level of educational inequality I heard about when researching ‘The underrepresentation of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller pupils in higher education’, for King’s College London. Perhaps the starkest finding though, was the scale and severity of discrimination faced by pupils from these communities in UK schools.

It got me thinking about how prejudice develops amongst pupils more generally, and I’ve since been getting to grips with a body of research on the topic that seems to indicate that even very young children display implicit prejudice to the same level as adults. It’s a conclusion that has challenged many of my assumptions about how and when prejudice develops, which were that:

- I generally thought that young children aren’t prejudiced, that they ‘don’t see or care about difference’ and are generally accepting of one another regardless of race, gender, religion or background. In retrospect I realise I assumed this despite having seen children – even in reception classes, being unkind about such things.

- I also assumed that where young children displayed prejudiced attitudes or behaviour, they had probably learnt them from their parents’ explicit prejudice. It would therefore be quite difficult to counteract that learning as an educator or other adult. As I will argue in my second blog in this series, this also affected my views on how to address prejudice.

While there might be a kernel of truth in each of these assumptions, the research presents a more nuanced picture.

At what age do children develop prejudice?

Firstly, children as young as three or four years old have been shown to exhibit gender stereotypes, racial prejudice and preference for their own race. In 2012, researchers found that children as young as three show an implicit own race bias. In this experiment, children were shown racially ambiguous faces that had either a ‘happy’ or ‘angry’ expression and asked to categorise the faces as ‘white’ or ‘black’. The white children (i.e. the socially advantaged group in this case) were more likely to categorise the ‘happy’ faces as ‘white’ and the ‘angry’ faces as ‘black’. Crucially, these results and results of other experiments which found implicit bias in young children were strikingly similar to the results of adults in the same experiments. Furthermore, when black children (the socially disadvantaged group) were tested, they did not show a bias in either direction.

If young children are aware of and biased about racial groups it’s clear my assumption that young children were unbiased or free from prejudice is flawed.

Where do children ‘learn’ this bias from?

I also previously assumed that young children exhibiting prejudiced attitudes or behaviours were simply replicating attitudes or behaviour modelled – or even explicitly reinforced – by their parents. However, two findings from the research discussed above throw this assumption into question:

- Most children in the race majority, socially advantaged group (i.e. white children) showed bias and prejudiced attitudes, but it’s unlikely that all of their parents explicitly promote prejudicial views.

- Children showed similar levels of prejudice to adults. However, if prejudice developed as a result of parental influence and reinforcement, you would expect to see gradually increasing levels of prejudice as modelling and reinforcement continued to encourage it.

It therefore seems the origin of children’s biases must be more complex. Sheri Levy, an expert in the development of prejudice certainly believes so:

“Research suggests that being raised in a prejudiced environment does not necessarily translate into developing prejudiced attitudes, nor does a tolerant environment necessarily lead to tolerant attitudes.”

There are many theories about how children develop prejudice. While there are too many to fully explain here, those I have read have highlighted some thought provoking, and sometimes surprising, findings:

Which categories ‘stand out’ plays an important role in how children develop biases: children hold biases about things like race, gender and attractiveness but tend not to stereotype based on other things such as height, hair colour or left/right handedness. It appears some categories are more ‘salient’ than others.

There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, categories have to be perceptually obvious and easily classified into group if children are going to develop stereotypes about them: babies can discriminate race, gender and attractiveness whereas traits such as left/right-handedness are less physically apparent and characteristics like height are more regularly distributed. Secondly, adults focus implicitly and explicitly on certain groupings rather than others. A common example is seemingly-innocent phases that emphasise gender, such as ‘good morning boys and girls’. A more extreme example is segregation by race, and while official racial segregation is hopefully rare these days, it does occur when neighbourhoods – and therefore schools – are ethnically homogenous. When we focus on (or separate) particular groups, we send children a message that these categorisations are important, and children will ascribe meaning to them. Children may even hypothesise possible differences between groups, with their hypotheses favouring their own group, due to the drive to see one’s ‘in-group’ positively.

Children can learn prejudice from adults’ unconscious, non-verbal behaviours: most adults hold implicit racial and gender biases and these biases may affect adults’ unconscious, non-verbal behaviour. For example, a white woman with a negative implicit bias against black men may unconsciously speed up or move away when walking past a black man in the street. Experiments show that children are sensitive to these non-verbal behaviours.

Researchers showed children a video of two similar women being given a present by a third person. The third person showed positive non-verbal signals toward one woman (smiling, leaning in, warm tone of voice) and negative non-verbal signals to the other woman (frowning, leaning away, cold tone of voice). The children were then asked which of the two woman who were offered gifts, they preferred. The children preferred the woman who had received positive non-verbal signals and, when asked who the gift should be given to, were more likely to choose this woman.

In an extension of the experiment researchers also found that if they introduced the ‘best friend’ of each of the two women, children preferred the best friend of the woman who received positive non-verbal signals compared to the best friend of the woman who received negative non-verbal signals. This demonstrates that not only do children make judgments about people based on other adults’ non-verbal signals, they extend these judgments to other group members. Therefore, even if parents or teachers avoid making negative, prejudiced statements about certain groups, they can still pass on implicit attitudes.

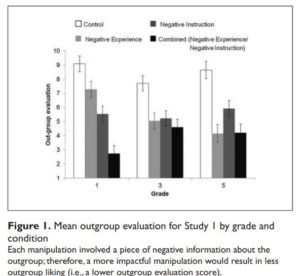

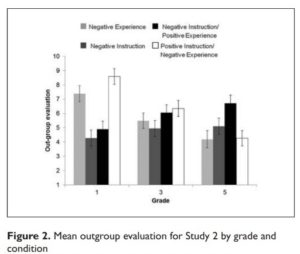

Younger children are more influenced by adults’ statements about out-groups than older children who are more influenced by their experience of outgroups: another experiment looked at how an adult experimenter’s statements about an outgroup (the ‘blue group’) and a child’s ‘experience’ of the outgroup influenced children’s perceptions of what the blue group were like. The ‘experience’ of the blue group was how many tokens the child receive from them. The researchers’ found that:

- Negative statements about the ‘outgroup’ – e.g. “Kids in the Blue group are really mean to kids in the Red group” – were more influential for younger children (aged 6 to 7 years) than a negative experience of the ‘outgroup’ (i.e. receiving no tokens from them). Meanwhile older children (aged 10 to 11 years) were more influenced by the experience than the adult instruction.

- If young children heard a negative statement from adults, but had a positive experience of the ‘outgroup’ (they were given tokens) they still rated the ‘outgroup’ more negatively. In contrast, under the same conditions, positive experiences trumped the negative statement for older children.

Children can influence their parents’ attitudes: A Swedish study in 2016 was the first to examine whether parents were influenced by their children’s attitudes in the same way that some research shows children are influenced by parents. The longitudinal study examined parents and adolescents (with an average age 13 at the start of the study) over two years and found that the adolescents’ attitudes towards immigrants impacted on the parents’ attitudes (and vice versa). Specifically, measures of adolescents’ prejudice and tolerance predicted change in their parents’ prejudice and tolerance over time. This challenged previous thinking that parents’ impact on their children’s prejudice was a unidirectional relationship.

This may leave teachers and educators wondering what they can do to help. Fortunately, there is some research on this topic and it is important to look at this carefully given that some well-intentioned activities aimed at reducing prejudice can have the opposite effect. The next blog in this series will explore the ways that schools and teachers can help reduce prejudice and foster tolerance in their pupils.